In 1981, my dad ordered a Chevy truck from our small-town dealer. To cut costs, he insisted it be stripped of all amenities, including the truck bed, opting to weld a homemade flatbed to haul hay and pull cattle trailers. Years later, when it was not being used on the ranch, it became my school truck.

On most school days, reminders of my working-class status were right beside me. A lariat rope or a pipe wrench on the seat; not exactly the symbol of privilege or status I saw in movies back then, but every day from November to February, my shotgun behind the seat suggested a different kind of wealth: the freedom of hunting wild birds in wide open ranch country. Sometimes, I’d tap into those riches as I drove the dirt road home in the evenings, parking in the ditch before darting into a ravine or fence row to chase pheasants.

Hunting wild birds was my passion even when I was a young boy, and by the time I was ten, I was sneaking out with my dad’s M42 Winchester. By the time I got to high school, I was pretty damn good at it. Although I didn't fully grasp the nuances of real dog work, I had a half-lab, half-springer named Daisy, and together, we learned the intricacies of chasing pheasants in the grasslands of the high plains.

Occasionally, my father used that austere truck to haul my brother and me to what felt like another world, his friend's ranch where the beautiful creek bottom was covered with giant old cottonwoods—enormous trees that were used as corral corners for the big Texas-to-Montana cattle drives of the last century.

These groves were on the edge of quail country, and chasing the native covey birds through the trees and brush was mesmerizing and presented a new challenge. My dog behaved differently, and the birds held tighter. When I was fortunate enough to harvest quail, I cradled them as if they were exotic gems from a far-off land—a reverence that remains with me today.

I got another rich kid break in my sophomore year of high school when Mr. Leach, my high school football coach, needed some company on a long trip to quail country many hours to the south and east. He had a fine Brittany, and I said yes in an instant. That was my first experience with a good pointing dog, and I was instantly hooked.

By the time I reached college, my addiction was worsening. There were birds on the ranches outside of town, but I lived in a dorm room and needed a pointing dog. I searched classified ads for a bird dog, gathered every bit of cash I had, drove 35 miles, and bought a 10-month-old Brittany for $125.

The shivering runt of the litter was tied by a chain to a stark outdoor kennel. He needed rescuing, and I needed a friend who could hold a point. Neither of us could afford to be picky. I named him Mitch, and the next day was shooting birds over his points and then learning to sneak him into my dorm room.

That was a magic place and time, with its wild birds and ranchers who granted easy permission to chase coveys that darted over hills in the soft fall light. It was better than money, but like a kid with a fresh $100 bill, I often held it up to the light and then close to my nose, breathing it in to make sure it was all real.

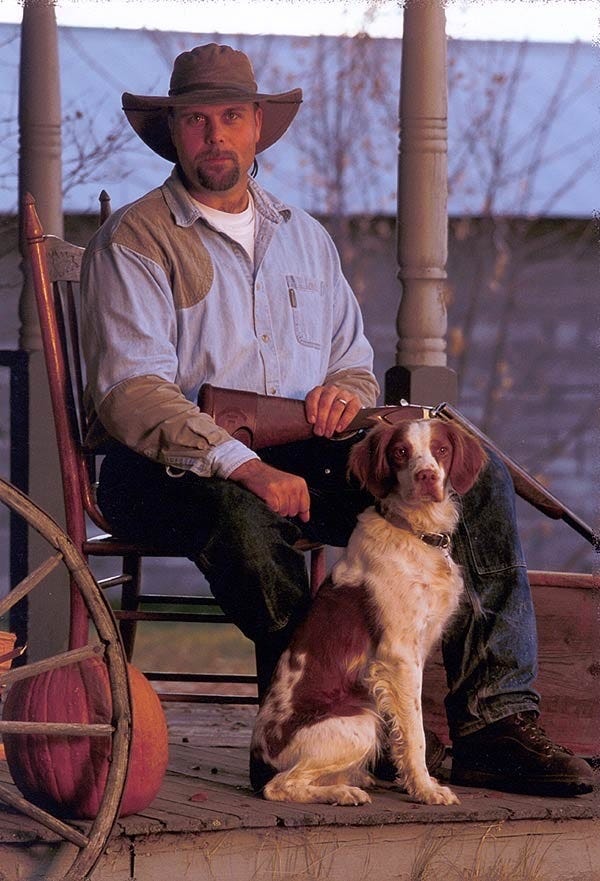

But college did not last forever, and as I moved on to find my place in the world, Mitch was thrilled to move to the ranch with my parents. Before long, I chased a dream to Montana, and once there, I almost immediately began searching for a new Brittany. Just as before, I found a listing in the local paper, drove to Missoula, and returned home with Ruark, the Brittany puppy that would be my hunting companion for the next 16 years.

Ruark was a big runner and covered a lot of ground. With him, I discovered the vastness of our incredible American inheritance. A 640-million-acre estate, too much of it already pot-marked and two-tracked, but some of it still wild and unspoiled. I was exploring our public lands and discovering some of the finest wild bird hunting on the planet. Living in Montana, pulling in just barely enough to buy shotgun ammo, I felt richer than every one of the mid-90s tech bros who were making millions from the internet boom.

This new land allowed me to trek 20 miles in a single day. In most places, I granted my own permission. Even after many long days, I stood on high points and saw another month’s worth of vastness.

I loved hunting sharptail, huns, sage grouse, chukar, quail, and mountain grouse in the expanse of the West. I unfolded maps with public land parcels measured in dozens of sections. I camped where I wanted. Walked for days on end. Learned where sharpies lived and what they ate. Watched them travel many miles on a single flight. I chased hun coveys over high ridges and through skree fields. It was country big enough for an army, so Ruark and I recruited more dogs. Any random day was a priceless adventure in a country too beautiful to describe. I had to pinch myself, and still do. I own this amazing place, right along with every other American.

I often mentioned this incredible shared wealth to old bird-hunting friends and one of them made a living selling shotguns. Through his work, he had hunted with very rich people across the pond, at castled old-world estates owned by tweed-wearing people with last names that translated to “only the royalty gets to do this in Europe.”

That old money pompousness was not his style, so he gladly accepted my offer for a hunting trip in Montana. On one cold October evening, the dogs were curled up in our little camper after a strenuous day not far from the Missouri River breaks. He and I sat near a small campfire under the stars, looking up and marveling at the constellations. He grabbed my arm, looked me in the eye, and said, “Don’t ever believe it gets any better than this.” He’d seen real wealth and knew the truth: American public landowners are richer than all those royal snobs in their fancy castles.

I have been fortunate to spend hundreds of days on our vast public estate. Exploring new haunts. Climbing new mountains. Seeing dogs point 9 or 10 different species in a year. Wearing out boots every year. Never asking for permission.

A monetary system that can measure this sort of wealth will never exist.

The real beauty is that we all own these places. We all have the same permission. This public land of ours is the great leveling field, perhaps the last one left in the world—the farthest thing from an exclusive club. You don’t need an aristocratic last name or an old-money trust fund. Tech bro net worths, shiny cars don’t mean shit out here. No one cares what color you are or how many PhDs you have. Even a kid in a ranch truck is wealthy.

The truth is, all of us Americans were born rich.

Love this! I grew up in southern and central Idaho chasing pheasants with my dad and a red setter named Brandy. After a sojourn in Arizona and a career in law enforcement, I returned to the Northwest and moved to the Bitterroot 18 years ago. We are on our second Brittany now, and my three kids all grew up with the incredible legacy of Montana public lands. We are determined to stand up for the public lands we hold dear!

Yes, a thousand times yes....stewardship responsibility and thankfulness for all the gifts of public land!!!!